I am someone who wants to see all the information before making a decision.

This is a debilitating character flaw in a profession where every decision is based on limited information and unknowable future outcomes.

Over the years, I have worked hard to overcome this… Who am I kidding, I’m still working on it.

When I first started investing, I wanted all the answers before placing a trade. I wanted certainty.

But investing is a game of probability, not certainty.

It can seem so easy from the outside looking in. When you know exactly how the story ends, everything is obvious. Hindsight is 20/20. Just buy what goes up and sell what goes down right?

Every past market crash looks like an opportunity, while every future market crash feels like risk.

In reality, we are all just a bunch of historians trying to put together pieces of the past to solve the puzzle of the future. But the future is inherently uncertain, no matter how hard we try and convince ourselves otherwise.

That’s all it is – just a bunch of historians pretending to be clairvoyant.

Just this week, we had the SVB banking crisis. Suddenly we are flooded with experts blatantly pointing out the facts….AFTER THE FACT. But being able to tell a story after all the information is already on the table is not how you make money in this game.

People say investing is like chess, but in chess, all information is known, and there is a right and wrong way forward at any point. It’s based on computation.

Investing is more like poker; you need to lean into the uncertainty.

“Both poker and investing are games of incomplete information. You have a certain set of facts and you are looking for situations where you have an edge, whether the edge is psychological or statistical.”

– David Einhorn

In both investing and poker, your success over the long run will come down to your ability to make the best possible decisions based on the available information – quickly.

If you are waiting for ‘all the facts’, you’ll be left on the sidelines.

Thinking In Bets

As an ex-professional poker player with over $4 million in lifetime earnings, Annie duke has spent countless hours improving her decision-making process.

In her book ‘Thinking in Bets’ she speaks about specific cognitive biases that impact how we view our decisions.

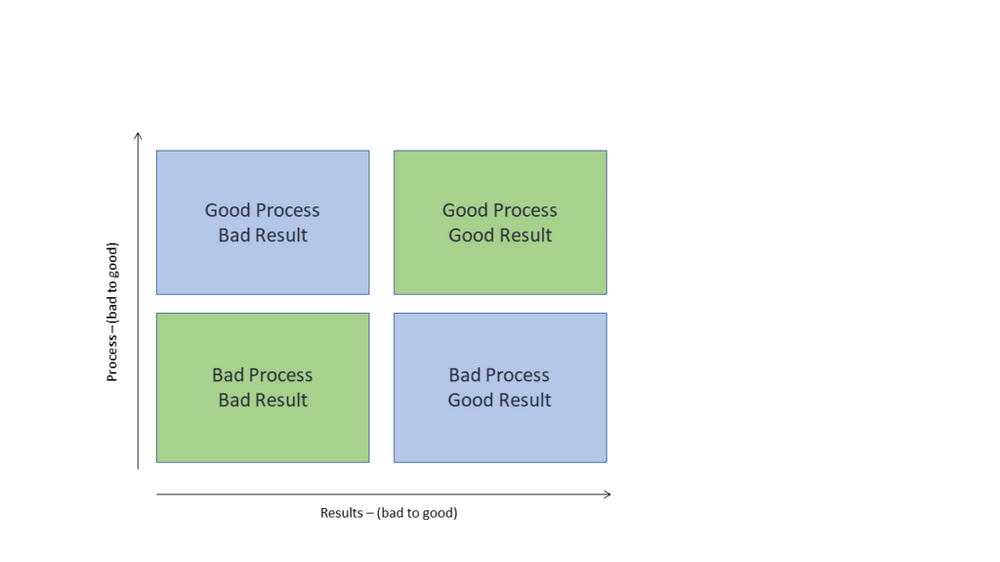

‘Resulting’ is one such cognitive bias.

Put simply, ‘resulting’ refers to our tendency to use the outcome of a decision to determine whether or not we have made the right choice.

There are a number of issues with this.

1. Bad Decisions Have ‘Good’ Outcomes All The Time.

Imagine you’re late for work and approaching a crossroads as the traffic light turns red. You decide to run the light. You get through just fine and make it to work on time.

Was that the right decision?

The outcome was favourable, but you risked potential death to shave 2 minutes off your commute….. questionable decision-making at best.

2. Reinforcing Bad Behaviour

Previously successful outcomes convince you that it is a good decision.

Sticking with the driving analogies. Imagine you decide to drive home after a few drinks. You get home just fine. So you do it again and again. The successful outcomes compound to the point where you convince yourself this is a perfectly safe thing to do. You become more and more reckless until, eventually, disaster strikes.

Just because the probability of a negative outcome (getting caught, crashing) is low doesn’t mean the risk/reward payoff makes sense.

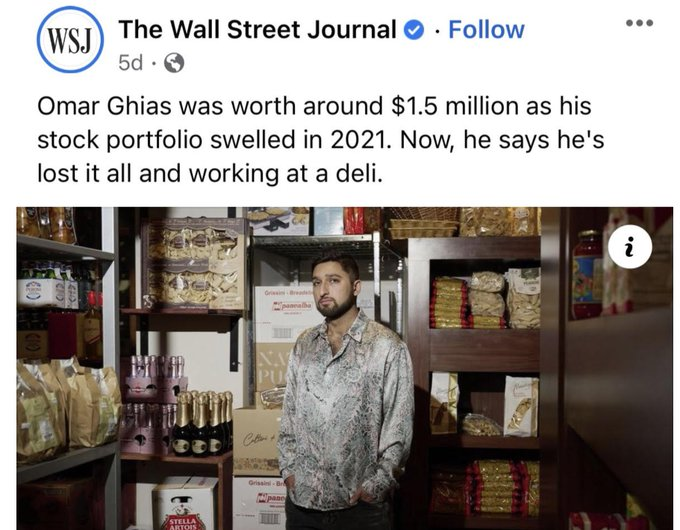

We see this in investing all the time. Traders make statistically questionable decisions that work out in their favour. The initial positive results reinforce the risk-taking behaviour until they eventually get blown up.

Bad decisions can play out in your favour for a long time, but eventually, the statistical probability will catch up with you.

Don’t be like Omar.

Download My FREE Investing Ebook

3. The Element of Luck

In poker, you can play a hand literally perfectly and still lose because there’s this luck element to it. Most decisions in life work the same way.

Ignoring the impact of luck means we convince ourselves that we made the wrong decisions when in reality, the decision was correct; we were just unlucky, or vice versa.

Imagine you have a trick coin that is heavier on one side, so it comes up ‘heads’ 90% of the time. If you place a bet with someone and the coin comes up with ‘tails’, was that a bad bet? No, you were just ‘unlucky.’ Every decision is based on probability, but the probability won’t always work in your favour.

A 90% chance you will win is still a 10% chance you will lose.

Losing doesn’t automatically make it a bad decision.

Focus on the process

We need to focus on the decision-making process, not the outcome.

The flaw is obvious.

Given that the outcome is unknowable at the time of making the decision, using it as the sole means of judging your decision-making process is moronic.

Every decision is based on probability. You want to select the options with the highest likelihood of a positive outcome. But even if you do this, you can still lose.

That doesn’t mean you have made the wrong decision. It just means that the probability didn’t play out in your favour in the short run, but if you keep making good decisions, the statistics will play out in your favour over time.

This is true in your career, dating, investing, EVERYTHING. Not every move will be a ‘winner,’ but if you keep making well-thought-out decisions based on a process that is true to your values, these decision will compound and work in your favour over time.

‘The more I practice, the luckier I get.’

-Gary Player

3 Ways to Make Better Decisions

You can never be 100% certain a decision will work out in your favour, and you don’t need perfect information to make a high-quality decision.

Here are 3 things that helped me.

1. Does This Decision Even Matter?

Years ago, I was doing up a bathroom in my house. I spent days trying to pick out taps for a sink (anyone who has ever done up a bathroom will know there are somehow about 9000 options to choose from).

Obviously, I’m not deeply passionate about faucets – I just wanted to make the right choice.

But spending time meticulously choosing the right option is an inefficient use of your limited resources if the outcome holds no value.

Sure, you made the right choice, but two weeks of your life have gone by in the process.

To counteract this.

Ask yourself, ‘Will this decision affect my happiness in a week’s time’.

If the answer is no, make the decisions quickly.

2. Narrow your Focus

I have spoken previously about the ‘paradox of choice.’ The idea is that the more options we have, the harder it becomes to make a decision.

To counteract this, set out your criteria and reduce your decision to the two best options.

Our brains are much more efficient at making binary, either/or decisions.

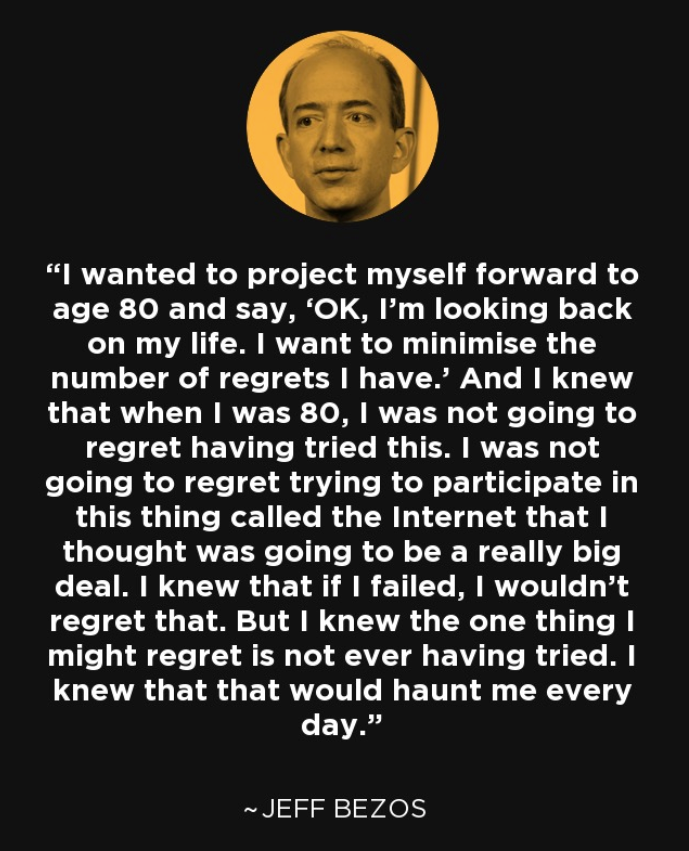

3. Regret Minimisation

We all have different versions of ourselves.

The comedian Jerry Seinfeld gives a great example of this in his skit about ‘Night Jerry’.

‘Night Jerry’ wants to stay out all night and go to clubs, while ‘Morning Jerry’ just wants to wake up not feeling like death.

The same person – two deeply opposing views.

The idea of regret minimisation feeds off this idea. What ‘current you’ wants and what ‘future you’ wants are often very different things.

Ultimately ‘future you’ is a more rational representation of who you truly want to become, so many of your decisions should be outsourced to ‘future you’.

When making difficult decisions, ask yourself.

‘In x amount of years. Will I regret this?’

Jeff Bezos famously credits this for many of his best decisions.

When asked how he decided to take the leap and start amazon;

Most of the biggest decisions in my life have been made using regret minimisation. They haven’t all worked out perfectly, but I regret nothing.

Most of the things holding you back in the short run will hardly seem relevant as you widen your lens and focus on the bigger picture.

Let future you decide.